“I was made in Indonesia but assembled in Thailand” — that’s the joke I often make about my origin story.

My parents were living in Jakarta, Indonesia when I was conceived. My dad was working for a Thai conglomerate with international operations and had been transferred there a couple of years earlier. But when my mom became pregnant, she had to make a long journey back to her rural hometown in Sakon Nakhon, northeastern Thailand, to give birth to me — and again three years later when she had my younger sister.

My mom comes from the Phu Thai, an ethnic group found across parts of southern China, northern Vietnam, Laos, and northeastern Thailand. One of their customs is that women must return to their parents’ home to give birth — which, in my mom’s case, meant a small rural hospital near her village. Another tradition is to bury the placenta of a newborn at the base of the stairs of the family’s stilt house, a symbolic act to ensure the child will always find their way home. Both mine and my sister’s placentas were buried there.

Mom’s lineage is fairly straightforward. Her grandparents boated down the Mekong and Songkhram rivers from Laos into Thailand long before national borders officially drawn. She often described herself as Lao rather than Thai. She even used to joke with friends that my siblings and I were “Chor-Por-Lor” (จปล.) — acronym for Cheen-Pon-Lao (จีนปนลาว), meaning “Chinese-Lao mix.” It was a cheeky pun on Chor-Por-Ror (จปร.), the acronym for the famous Chulachomklao Royal Military Academy (โรงเรียนนายร้อยพระจุลจอมเกล้า).

Dad, on the other hand, is three-quarters Teochew Chinese with one-quarter Northern Thai. His mother — my Ama — was half Chinese-Thai. Dad used to tell me that Ama’s mother, my great-grandmother, had once served as a lady-in-waiting to the Lampang royal family before the city was annexed into Siam in the late 19th century. Great-grandma passed down her knowledge of palace etiquette, teaching Ama how to sing and dance like a proper Lampang lady.

Anyway, Ama’s life was far from royal. According to dad, she started working at a tobacco factory when she was 12 years old, and picked up smoking on the job. She kept the habit for more than 50 years before quitting in her mid-60s. Ironically, she lived into her late 70s and died of causes completely unrelated to smoking. She also picked up black magic — including acquiring and roasting a dead fetus, and performing incantations to make her own Kuman Thong — a child ghost whom she calls upon for various supernatural errands.

During World War II, Ama joined an elephant caravan from her hometown in Nakhon Sawan and traveled south to trade rice. Somewhere along the way, she met Agong — my grandfather — who had arrived in Hat Yai by boat from Shantou, China in the 1940s, likely fleeing famine. They eventually settled in Narathiwat, one of Thailand’s southernmost provinces. Being Buddhist Chinese-Thais in a predominantly Muslim Malay-Thai region wasn’t exactly smooth sailing. Dad recalled how he and his Chinese mates often got into fistfights with local Muslim kids.

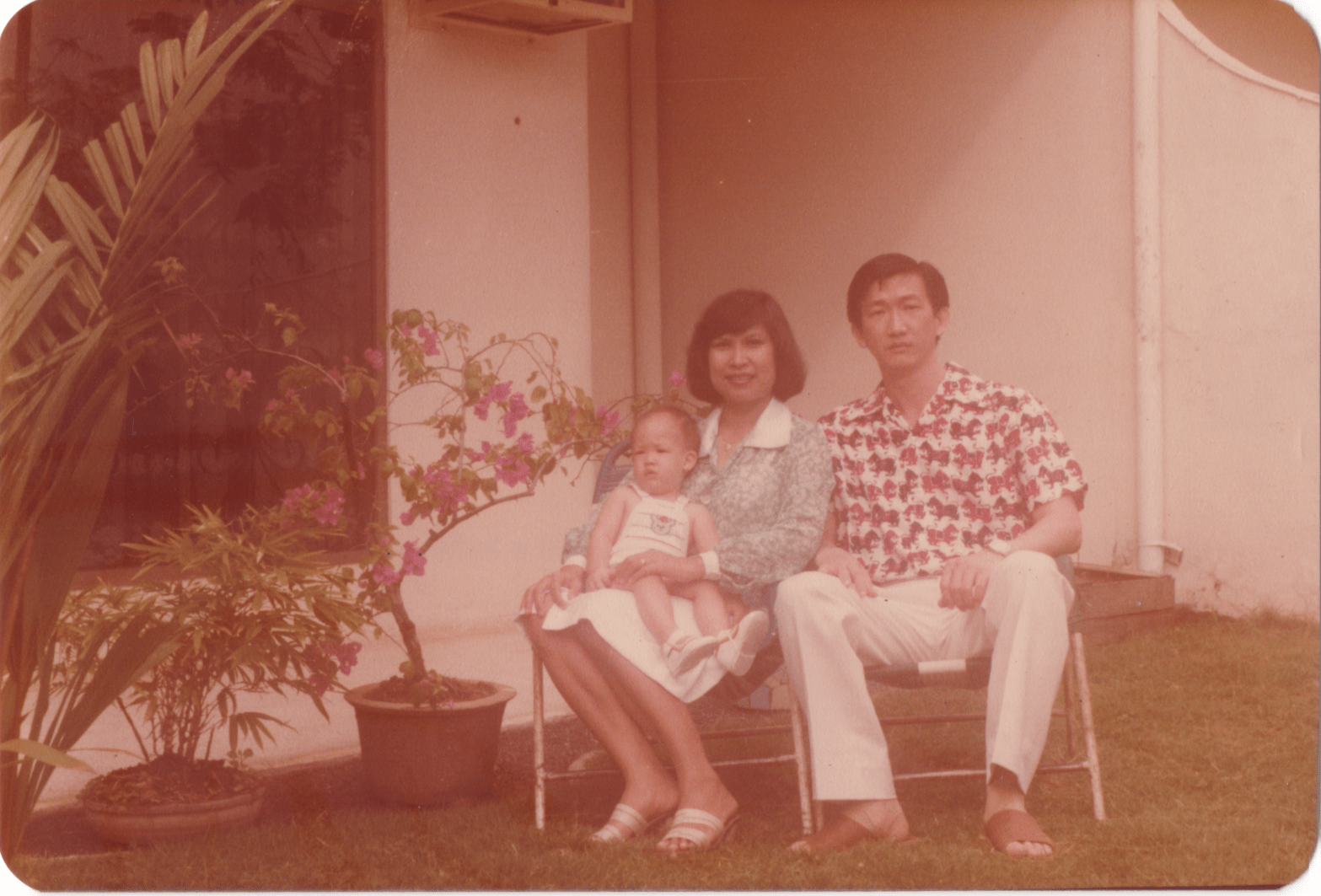

And here’s the long story short — with a plot twist: this southern Thai-Chinese boy and northeastern Lao-Thai girl met in the Philippines while pursuing their Master’s degrees — he studied business, she studied English education. They got married in Thailand, then began a well-stamped chapter of their lives: first to Indonesia (where I was conceived), then to Singapore, back to Indonesia (where my sister was conceived), then Singapore again — where my baby brother was born. But by that time, my mom’s parents had already passed away, which meant she was no longer bound by the Phu Thai tradition of returning home to give birth — so the pilgrimage ended with my brother.

Finally, in 1989 when I was 8 years-old, we moved back to Thailand — and that’s when I had my first taste of alienation. I couldn’t speak Thai at the time, but was thrown into a local Thai school while all the other Thai kids from my dad’s company who moved back were sent to international schools. I was the weird kid who didn’t quite fit in. And let’s be honest — no one’s lining up to play with the weird kid.

The reason I ended up in that local school? My dad had spent all his savings the year before on his father’s funeral. We were broke. We lived in a crowded house with one toilet shared by about ten people from my mom’s side, while just a 15-minute walk away, another house was packed with roughly the same number of relatives from my dad’s side. That’s when I learned how my family were actually pretty poor.